In Australia, these terms are being used to describe 17.9 million acres of burned land so far. While fires of this magnitude are certainly unprecedented, they’re far from unexpected. Climatologists have warned that the changing climate will have vast implications for our planet’s weather patterns and natural disasters.

But these warnings have done little to drive urgent climate action. More and more it seems that the world needs anthropologists, not climatologists, to understand the real trajectory of climate change, trends, long-term impacts, “Band-Aid” solutions, and to pinpoint the root causes. The reason for the magnitude of these fires is complex and certainly requires attention to climate, but it can all be traced back to one thing: How we grow our food.

Fire Begets Food

Humans have been influencing the land and environment for the sake of food for centuries.

Australia’s landscape did not always look like it does today. Historians and scientists can point back to a time when humans’ need for food completely altered the continent’s natural makeup.

50,000 years ago, Australian Aboriginals used “fire stick farming” as a way to hunt large animals. Equipped with torches, humans burned forests to drive out, trap and kill things to eat. This tactic happened on such an extreme level in Australia that humans were able to drive hairy rhinoceroses, massive birds, giant kangaroos, wombats, and other massive marsupials to extinction. Humans forever changed Australia’s plant and wildlife.

Sadly, this practice is still in use today and we’ve seen it continue in places such as Mali and Central African Republic. But a different form of “fire farming” is used on a much larger scale in the 21st century.

The modern global food system is dependent on open land because monocropped cereal grains are at the core of our diets. Growing rows of grain is cost-effective, it can be fed to animals, and it is easily turned into processed food. The agriculture industry and farmers of every kind have cleared trees at a rate of 5 million hectares a year to make room for crops like corn, wheat, and soy. The easiest way to do this is by lighting fires to burn trees, shrubs, and grasses and then clearing them to plant the monocrops. This is called swidden, or slash-and-burn agriculture. It has plagued farmers for centuries and it is exactly what is happening to the Amazon.

Food Begets Fire

Setting aside the lasting developmental and health implications of the global diet, the destructive land use practices to achieve this diet are 1) unsustainable and 2) the leading cause of climate change.

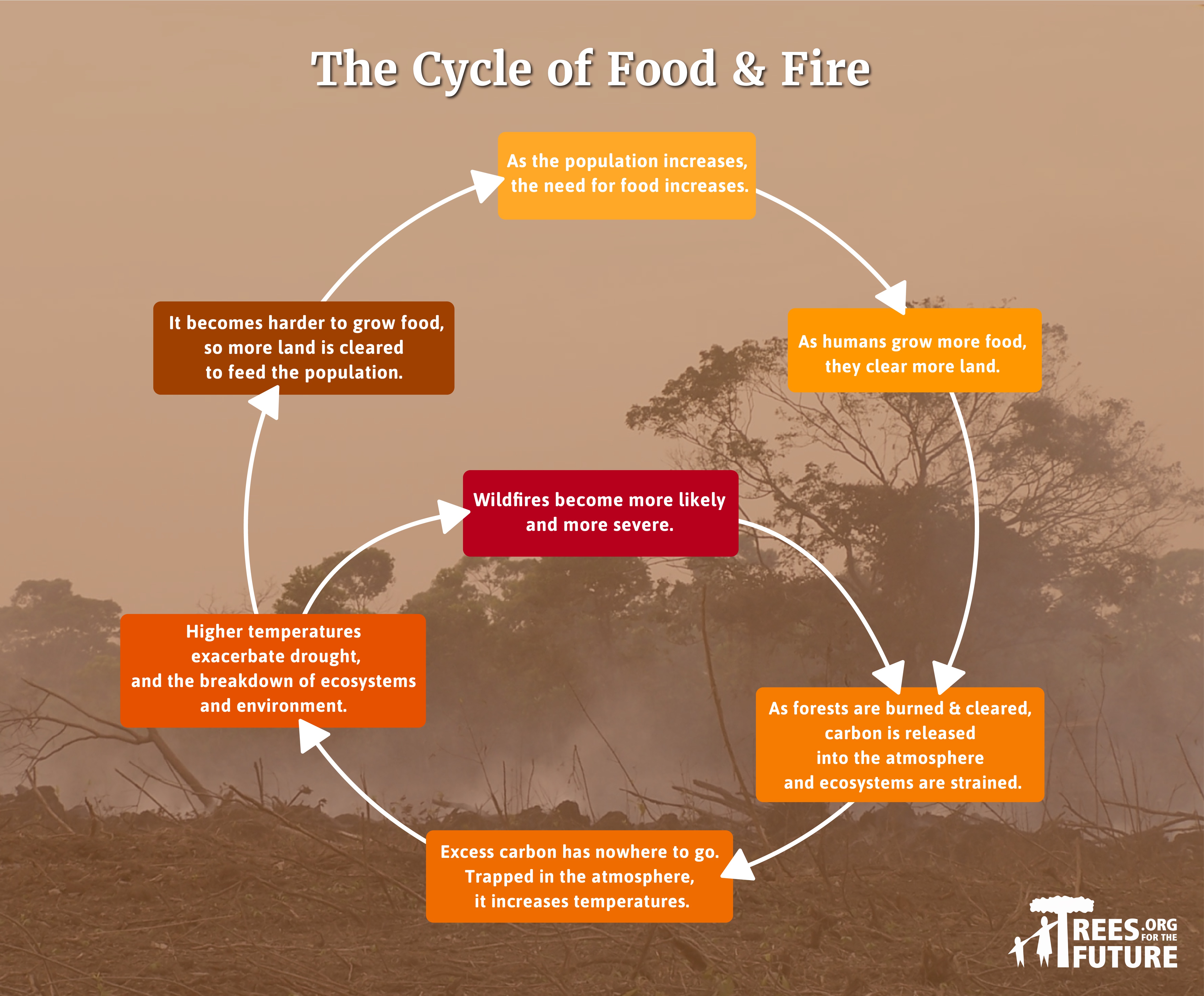

As the population increases, our need for food production increases. Humans work to grow more food and clear more land. As forests are burned and cleared, carbon is released into the atmosphere and ecosystems are strained. Excess carbon has nowhere to go and increases temperatures. Higher temperatures exacerbate drought and the breakdown of ecosystems and environmental health. It becomes harder to grow food in these conditions, so more land is cleared to feed the growing population. High temperatures and drought also mean wildfires are more likely to burn out of control. This negative feedback loop is cut and dry: fire causes warming, warming causes fire.

In a cruel irony, often the offenders on the ground do not experience the worst of these effects. Weather systems and patterns are liable to change around the world, affecting the most vulnerable people first. This is true for the smallholder farmers in Trees for the Future’s Forest Garden program. Farming families in developing countries are subject to the impacts of climate change with no control over seed supply, no crop insurance, and few municipal programs for a safety net.

Although, there is one major outlier in the disproportionate effects of climate change: Australia. Long-standing climatic predictions have suggested that Australia would be an exception – a developed country facing the dramatic repercussions of man-made climate change, despite its GDP. “The country was founded on genocidal indifference to the native landscape and those who inhabited it, and its modern ambitions have always been precarious: Australia is today a society of expansive abundance, jerry-rigged onto a very harsh and ecologically unforgiving land,” writes David Wallace-Wells in An Uninhabitable Earth.

Wood Burns, Woods Don’t

A healthy forest is full of wood and yet, it cannot burn.

Why? Consider how to build a campfire: A camper needs tinder, kindling, and fuel. Tinder and kindling are critical in turning a spark into a flame. Once the flame is truly established, the camper adds fuel to the fire in the form of logs and the logs are able to maintain the burn.

Even in the dry season, where there may be small isolated fires across a dry landscape, a forest should not burn uncontrollably. But today, many forests around the globe are surrounded by “tinder.” A common form of tinder is grazing grassland maintained for grazing animals like cow or sheep. Another is parched crops or what is left behind after harvest: crop residue, the stubble of a cut grain still attached to the root. Farmers around the globe – American, Iraqi, and Australian – are all too familiar with the danger a lightning storm poses in the dry season. A lightning strike can literally destroy hundreds of acres of a crop or grasslands in a matter of minutes. Put that field next to a forest during prolonged drought and a spark from a transformer or lightning storm has plenty of dry tinder and kindling to get started.

The Australian fires burning right now are countless. Fires are raging all over the country; bushland, forests, national parks, and farmland now burning were all parched in the wake of record-breaking heat and drought. The country is a veritable tinderbox, and with plenty of fuel in their path, little can be done to stop the fires as they envelope swaths of countryside.

How We Fix It

Food production is the problem, but it’s also the solution.

When the agriculture industry and smallholder farmers embrace sustainable farming methods, incorporate trees into the growing process, and find alternatives to monocropping, their impact on the environment will change for the better.

Farmers have historically fought suggestions of man-made climate change because of the implications for their bottom line. But as they start to feel the effects of a warming climate and recognize that land use is a major contributor to the problem, many farmers are turning a corner and becoming climate activists themselves. In Australia, nonprofit Farmers for Climate Action supports “farmers to build climate and energy literacy and advocate for climate solutions both on and off farm.” It’s groups like this that will be integral in shifting public understanding and support of a transformational food system.

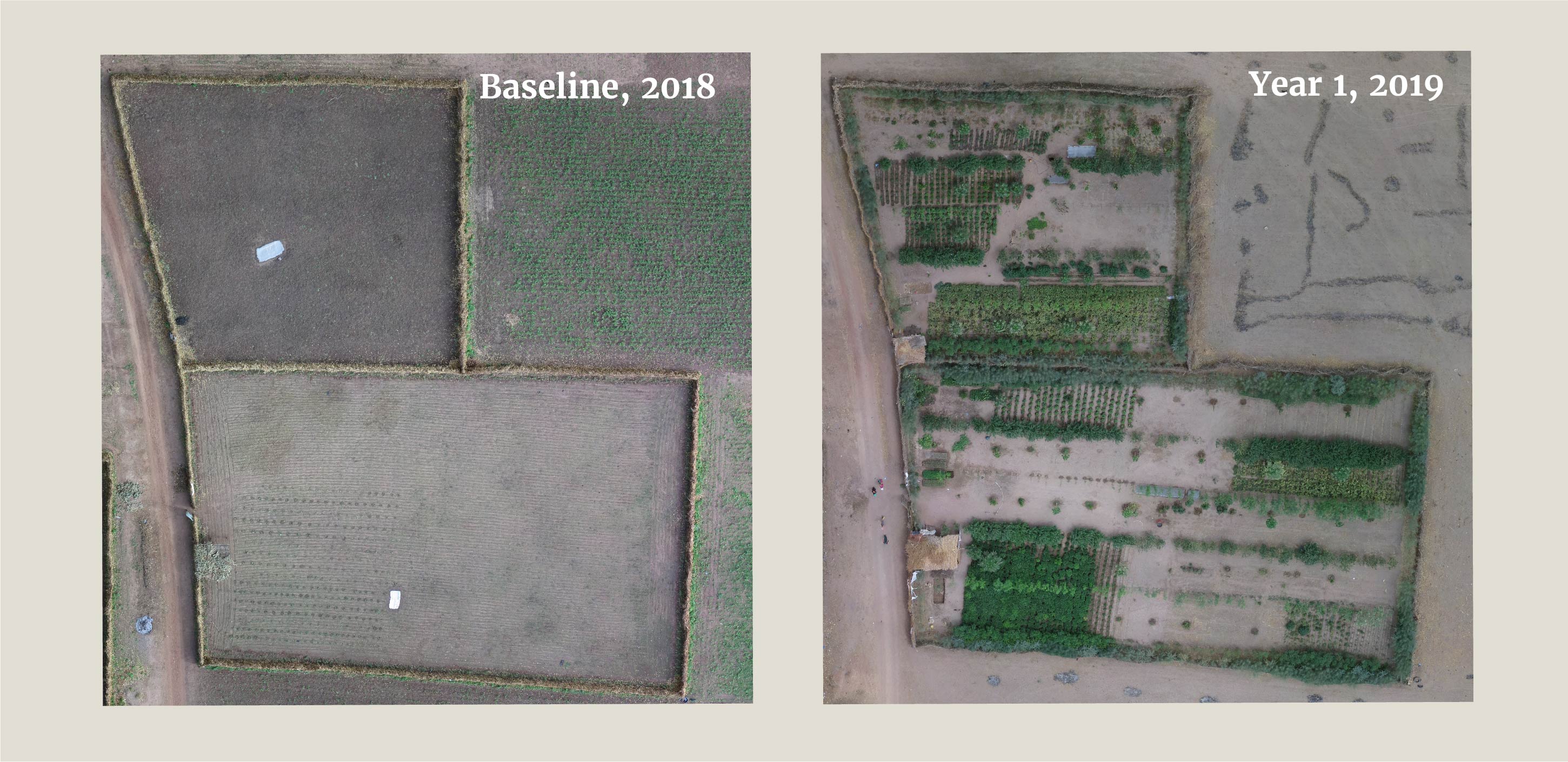

Trees for the Future works with farmers in Sub-Saharan Africa who have long practiced slash-and-burn tactics to clear land for monocrops like maize or peanuts. These farmers are contributing to deforestation, and the prolonged periods of drought they suffer through are evidence that they’re feeling the impacts of man-made climate change. Fortunately, shortly after they integrate trees and sustainability into their farming, these farmers see vast improvements in their soil health, biodiversity, and micro-climates. Abandoning monocrop techniques for agroforestry and regenerative methods (see below) also increases their production and incomes – proving that changing the way we farm does not translate to a decrease in profits, but rather the opposite. Much like financial diversity, crop diversity helps to ensure resilience in the face of unexpected challenges and environmental strains.

“Trees once provided natural protection, acting as dug-in soldiers shielding countries from typhoons, hurricanes, and monsoons. They covered the countrysides, cooled the land, brought the rain and channeled excess water back into the ground,” writes John Leary in One Shot: Trees as Our Last Chance for Survival (p. 124). “Trees provide both CO2 reduction and mitigation, serving as a nonpartisan weapon that is exempt from climate politics, whose beneficial existence is not subject to scientific evidence or debate. So their value should be recognized, right?”

When we stop clearing our trees and start embracing their benefits, we’ll see a shift in the negative climate trends plaguing regions subject to natural disasters. We can create a positive feedback loop wherein planting more trees and ending deforestation results in predictable weather patterns, healthier ecosystems, and fewer trees lost to unprecedented, catastrophic wildfires.

Learn more about Trees for the Future’s work with smallholder farmers, and visit their Forest Garden Training Center to learn how to implement regenerative agriculture practices.

Remember to give responsibly when donating to Australian wildfire response efforts.