“I am 38-years-old and it is in these last three years that I [learned] that the land of Boulel could allow the cultivation of other species apart from millet and peanuts,” she says.

Kaffrine is part of what is known as the Peanut Basin, a massive stretch of Senegalese farmland dedicated to peanut production. The region’s dependence on peanuts (and little else) presents several challenges and risks which Sokhna and her fellow farmers have lived through for years. Peanuts, millet, or any monocrop planted year after year deplete the soil of its nutrients without giving anything back. Over time, soil quality suffers and so does the crop. Farmers are left trying to earn a living off of a subpar crop in a market where everyone else is selling the same thing. Farmers clear more land and buy more chemical amendments in an attempt to increase their profits, further degrading the land they need to survive.

This way of farming destroys the land and traps the farmer in a cycle of poverty. And despite being credited with feeding the world, this approach to farming often means a farmer is unable to feed themselves. Sokhna recalls how she used to feed her family after the peanut harvest.

“I collected the rest of the peanut crops and made porridge for my seven children,” she says.

But today, Sokhna’s farm is not another dry patch of peanuts in Senegal’s Peanut Basin. Instead, her farm and the farms of 225 other women are dotting the Boulel landscape with rich swathes of green and her family is thriving.

As she says, the transformation started a few years ago when she and her neighbors joined Trees for the Future and adopted a new way of farming called the Forest Garden Approach.

The Forest Garden Approach is an agroforestry technique that focuses on protecting the land with trees and diversifying crops to improve both diet and income. Nonprofit Trees for the Future (TREES) trains farmers in the Forest Garden Approach over a four-year period. Local TREES staff work closely with farmers, providing them with the skills and knowledge they need to succeed long term. To date, TREES has helped more than 200,000 farming families adopt the Forest Garden Approach, planting more than 215 million trees in agroforestry systems around the world.

“Since 2019, I have had the chance to integrate this project and since then all my economic problems have been solved,” says Sokhna.

“With the Forest Garden today we grow vegetables like okra, chilli, eggplant, tomato, pepper, but also fruit trees such as lemon and papaya,” says Anta Gueye, a group lead farmer. The harvests don’t just feed her family, they make covering life-changing expenses like school fees possible. “All eight of my children have been in school for two years now.”

When the group shifted their focus from peanuts and millet to a diverse mix of fruits and vegetables, they gave themselves the opportunity to capture an untapped market in their area.

“Beyond food security for our families, we have become the main suppliers of vegetables to all the loumas,” says Fatou Diop, a group lead farmer. (Loumas is a Wolof term meaning weekly village markets.)

“Today, we have felt a very strong social and economic progression of households in the area,” says Mapenda Ba, TREES Technician Supervisor in Kaffrine. “The development of the area has intensified thanks to the female leadership born from the project.”

It’s long been clear that including women is key to sustainable development, and as Mapenda points out, the women of Boulel are clearly making a lasting impact. While women produce up to 80% of food for household consumption in sub-Saharan Africa, they are often not able to own land and can be left out of development opportunities. Trees for the Future projects are typically made up of about 200-300 farmers and the organization has a base requirement that at least 30% of participants are women in an ongoing effort to include women in the fight against hunger, poverty, and land degradation. Neighboring TREES projects within Kaffrine and across sub-Saharan Africa follow this requirement, often with all-women-groups of 25 or 30 throughout larger projects, but Sokhna’s group is unique as it is the first TREES project with 100% female participation.

“This is the first time in 50 years of life on Earth that I have seen a project involving only women, even one of the TREES technicians in the area is a woman,” rejoices Fatou.

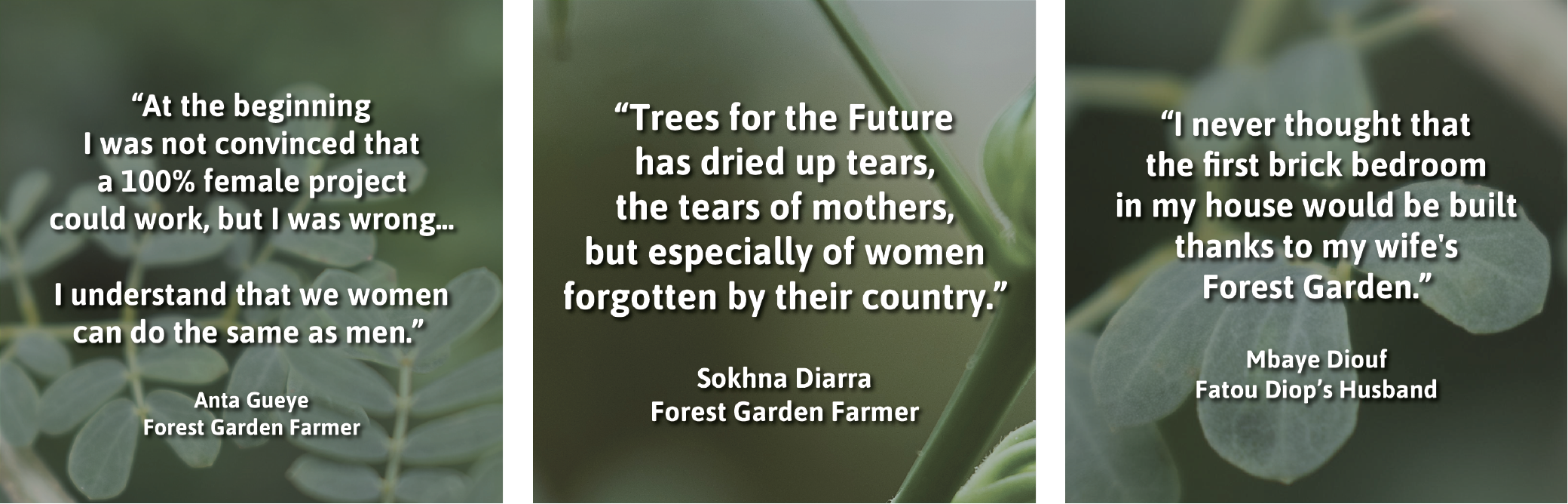

“At the beginning I was not convinced that a 100% female project could work, but I was wrong and I understand that we women can do the same as men,” says Anta Gueye.

As the women transform their land and livelihoods – and agriculture as we know it – they’re gaining the respect and admiration of their family and communities.

“I never thought that the first brick bedroom in my house would be built thanks to my wife’s Forest Garden,” says Fatou’s husband Mbaye Diouf.

“TREES has dried up tears, the tears of mothers, but especially of women forgotten by their country,” Sokhna says. “TREES did more than give us fish, you taught us how to fish.”

With the knowledge they need to thrive, Sokhna and her fellow Forest Garden farmers are sending their children to school, building new homes, and installing water basins in their Forest Gardens. Their farms are transformed, Sokhna herself went from zero trees on her one-acre Forest Garden plot to more than 3,000. In all, the 226 women have planted more than 1.5 million trees so far… and they still have two more years of training to go.

Make more success stories like this a reality. Support sustainable tree planting and lasting change for farmers in the developing world. Donate to Trees for the Future today.